I have always viewed the G7 currencies as satellite currencies orbiting the U.S. dollar, the central planet of the international USD centric monetary system. Among them, the euro and the yen are the largest satellites, the ones whose mass and influence most shape the USD led monetary field. Their movements are governed by the dollar’s gravitational pull, structured around three distinct layers of gravity: geopolitical, economic, and monetary.

Geopolitical gravity: Both Europe and Japan remain anchored within the U.S.-centric system of trade, security, and technology. When these structural forces shift, such as demographics, global supply chains, defence alignments, or technological standards, the euro and the yen adjust accordingly. Their orbit direction reflects deep strategic interdependence rather than cyclical policy decisions.

Economic gravity: The dollar’s growth cycle still defines global liquidity and capital accumulation. As the U.S. economy expands or slows, its gravitational pull shapes trade balances, earnings, and cross-border capital flows, setting the tone for the euro and the yen.

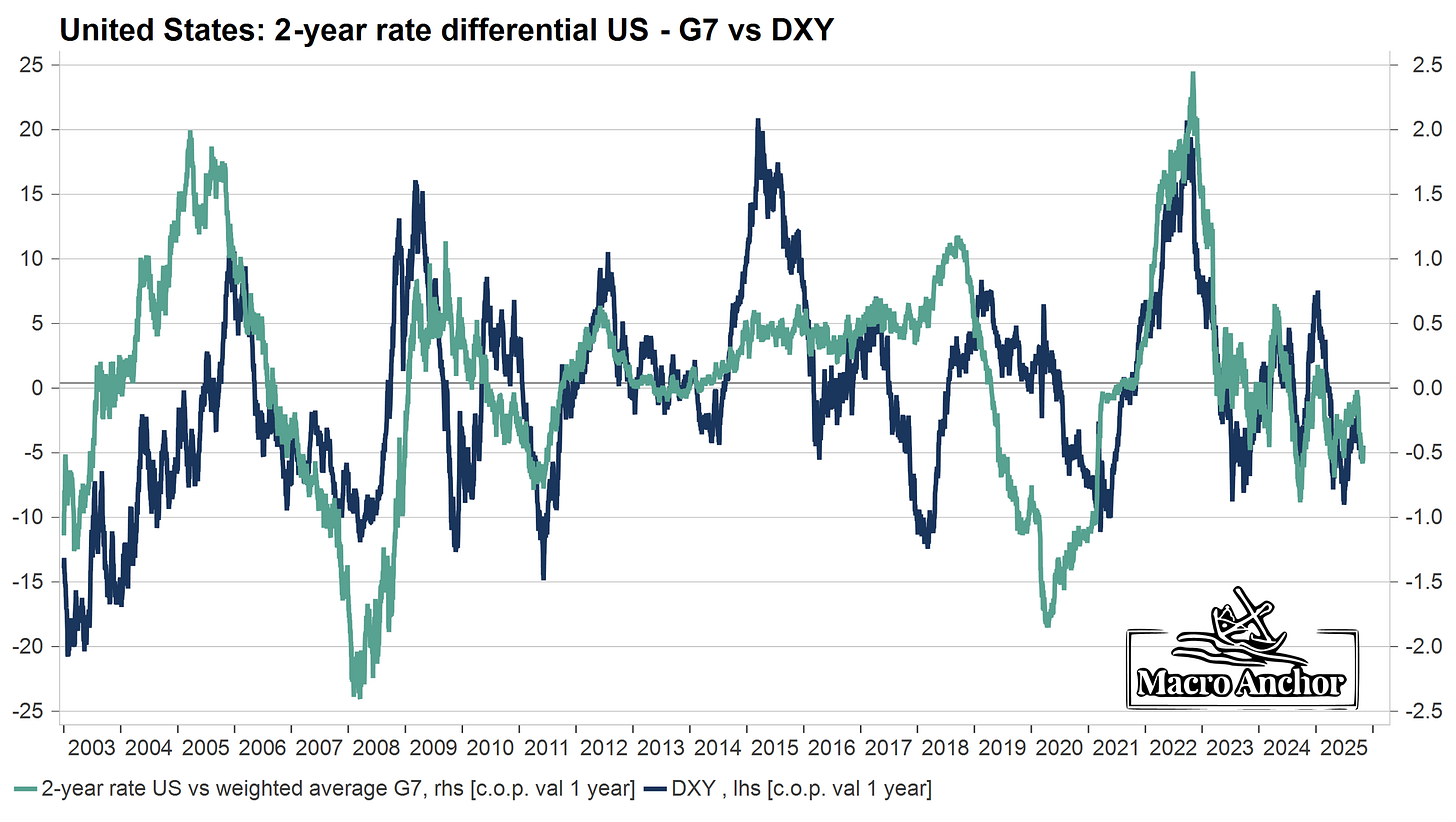

Monetary gravity: Finally, when the Fed moves, yield differentials shift instantly across these satellites. Yet orbits are not one-sided, the euro and the yen have enough mass of their own to exert counter-pulls. Divergence at the ECB or BOJ can alter global liquidity and risk sentiment, subtly reshaping the dollar’s own Orbit speed.

This is why the USD remains so closely correlated with interest-rate differentials between the U.S. and the G7 economies. The tighter the monetary orbit, the stronger the correlation. When that link breaks, it usually means force 1: geopolitical gravity is shifting.

An example of a structural change within force 1 is the European Union’s strategic turn after the election of a new German chancellor and Berlin’s commitment to raise defence spending to 5 percent of GDP. That was not a cyclical or monetary event but a geopolitical re-anchoring, signalling Europe’s attempt to redefine its economic model around defence, infrastructure, and domestic demand. Such regime shifts change the orbit itself, altering the balance between the euro and the dollar far beyond what short-term growth or rate spreads can explain.

Another structural change within force 1 is Japan’s demographic implosion. A shrinking population, negative household savings, and a collapsing export surplus are redefining Japan’s position in the dollar system. For decades, Japan’s savings and trade surpluses fed the U.S. economy; now the flow has reversed, and Japan increasingly relies on U.S. demand and capital inflows to sustain growth. The result is a gradual shift of Japan’s structural gravity.

This planetary framework helps explain the current divergence between the ECB and the BOJ: two institutions operating under the same gravitational field but responding differently to it.

The ECB and the Euro

The euro area is undergoing a structural transformation. Its old growth model centred on manufacturing and exports, is giving way to one driven by domestic investment and fiscal expansion. Europe is shifting from external to internal demand, and from factories to services. This transition is occurring under pressure. China’s deflationary dumping of industrial goods is flooding European markets, suppressing prices and compressing margins across key sectors. At the same time, the bloc faces political fragmentation, beginning with France, and a potential debt flare-up in countries such as France or Italy.

After having lowered real rates close to zero, broadly consistent with the euro area’s limited real-growth potential, the ECB now sits on the side-lines. From here, monetary policy will be guided less by inflation or output data and more by political cohesion and fiscal coordination among member states. The baton has passed from Frankfurt to the national capitals, from monetary to fiscal power.

In this context, the euro yield curve is likely entering a gradual and controlled bear-steepening phase, with long-term rates rising moderately to reflect the projected increase in public debt. The era of artificially compressed term premiums is ending. The ECB, having largely normalized policy, is expected to end its quantitative tightening (QT) soon, meaning it would resume reinvesting maturing securities rather than allowing them to roll off, a pause that would ease upward pressure on long-term yields and help governments manage their financing costs as fiscal policy takes the lead.

At her 30 October 2025 press conference, Christine Lagarde confirmed that the ECB kept rates unchanged and declared that policy is “in a good place.” She stressed that decisions will be made meeting by meeting, with no pre-set bias toward easing or tightening. Lagarde acknowledged modest growth momentum, citing a 0.2 percent expansion in Q3, and described inflation risks as “broadly balanced.” She also underlined that fiscal and structural policies must now do the heavy lifting, echoing the ECB’s growing recognition that monetary policy has reached its effective limit.

The euro area’s net-saver position reinforces that stability. Excess savings over investment continue to provide a steady domestic bid for sovereign bonds, allowing governments to fund themselves smoothly even as the ECB retreats. Several treasuries, notably France, Italy, and Spain, have shortened maturities and increased short-term issuance, while domestic banks and insurers absorb most of the new supply.

For now, there is no debt crisis, inflation is near target, and the ECB is not under political pressure. Paradoxically, at this stage of the cycle, the ECB appears more in control of its monetary policy than the Federal Reserve. From here on, the future of the euro will depend less on interest rates differentials and more on whether Europe can maintain fiscal cohesion and political unity during this transition from a monetary cohesion era to a fiscal cohesion era.

The BOJ and the JPY

Japan today represents another important satellite orbiting around the dollar. It is still bound by the same gravitational field but increasingly defined by imbalances within force 1, the geopolitical and trade layer. Geopolitically, Japan remains firmly anchored to the United States through defence, technology, and security. But structurally and commercially, it is also drifting inward: its population is shrinking, its household savings rate has turned negative, and its public debt exceeds 250 percent of GDP.

This erosion of Japan’s trade surpluses and savings base marks a historic reversal. For decades, Japan’s export surpluses and high savings fed the U.S. economy, financing deficits and supplying global goods. That era is ending. With a shrinking labour force, greater energy dependence, and rising import needs, Japan is moving from a creditor nation to a dependent ally, from one that once fed the system to one that now relies on it to eat. It no longer exports capital to the dollar world; it draws on it to sustain domestic demand. This is the clearest expression of a shift within force 1, the trade layer of the orbit.

Within that framework, the victory of Tainaka at the head of the Liberal Democratic Party confirmed continuity with Abenomics, fiscal expansion, monetary accommodation, and tolerance for a weaker yen in exchange for nominal growth and industrial revival. This is not simply an economic doctrine but a strategic choice: Japan is deliberately accepting inflation and currency weakness to preserve internal stability and its geopolitical role as the Pacific pillar of the U.S.-led order.

At his 30 October 2025 press conference, Kazuo Ueda announced that the BOJ left policy rates unchanged but said the likelihood of its baseline projection materializing had “heightened somewhat.” He added that the Bank “stands ready to raise rates if inflation and wages evolve as expected,” while stressing that there is no pre-set timeline for such action. Ueda described inflation as “moderate but not yet stable” and reaffirmed the need for accommodative conditions until wage dynamics prove durable. His caution underscored the dilemma: Japan cannot tighten without endangering debt sustainability.

The cost is a persistently weak yen, reflecting both the rate gap with the Fed and the deeper reality of Japan’s demographic and savings decline. The yen’s depreciation is therefore not simply a monetary story; it is the visible outcome of a shift in structural gravity. A country that once anchored the system through capital exports and technological leadership now sustains itself through policy accommodation and geopolitical dependency.

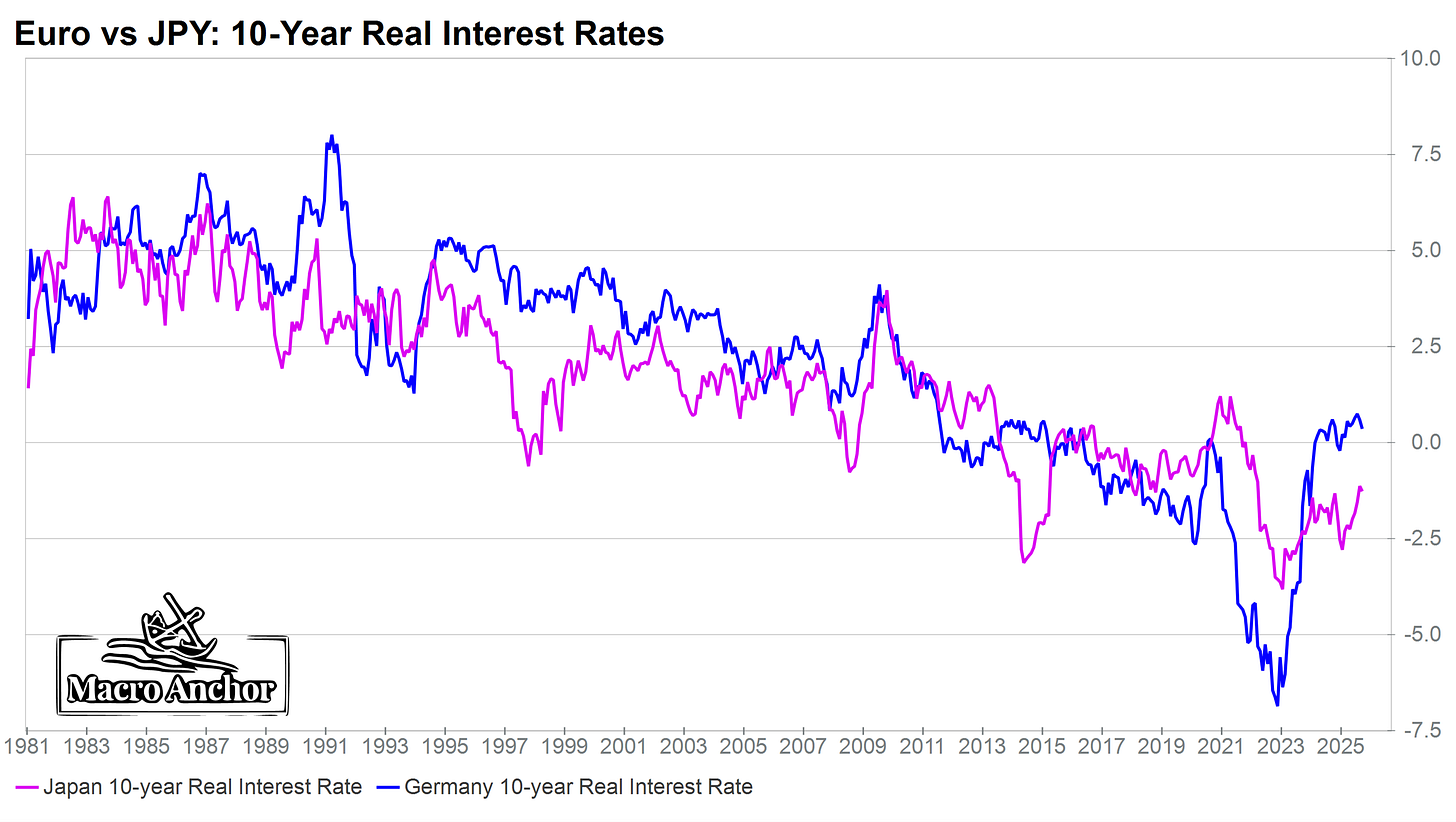

The contrast between the euro and the yen could not be clearer, and the chart below captures it perfectly. Europe has reached a point of monetary equilibrium, where real long-term rates have normalized around zero and the ECB can afford to wait, shielded by fiscal cohesion and political support. Japan, by contrast, remains trapped in a negative-real-rate regime, where every attempt to tighten risks destabilizing its debt and exposing its demographic decline.

In gravitational terms, the euro’s orbit has stabilized, balanced between fiscal expansion and cautious monetary restraint, while the yen’s orbit is shifting toward a more inflationary setting, one driven less by growth and more by the slow erosion of Japan’s savings, debt dynamics, and demographic constraints.

Regards,

Andre Chelhot, CFA

Editor,

The Macro Anchor

Better to use inflation swaps.