Weekly Macro and Policy Wrap-Up

The End of the Fiat Illusion — From Benjamin Strong to the Bi-Polar Monetary Order

When I launched Macro Anchor this summer, it was out of conviction that we had entered a regime shift, an irreversible transformation in the global economic system. At the time, most analysts were still debating inflation prints and rate cuts. I saw something deeper: the end of the era of moderation and the beginning of a world driven by fiscal dominance, financial repression, and geopolitical fragmentation. My first viral post, Trump’s Benjamin Strong Is Coming, So Is the Final Phase of the Bubble, reached more than 500 likes on LinkedIn and marked the birth of this project. In it, I argued that if Trump returned, he would appoint his own Benjamin Strong, a figure ready to flood the system with liquidity, suppress interest rates, and create one last euphoric asset boom before the inevitable reset

We now have him: Stephen Miran. A supply-sider with a trader’s temperament and faith that growth and confidence can out-run arithmetic, Miran is the modern echo of Benjamin Strong. He is precisely the kind of policymaker I described months ago, someone who will push easy money until belief itself becomes policy. His appointment as a Fed Governor confirms what I predicted from the start: that the next phase of this cycle will not be managed by technocrats but by pragmatists who view debt monetization as national strategy. The final phase of the bubble is no longer a metaphor; it is being engineered in real time.

Over the past three months Macro Anchor has traced the anatomy of this shift. We began with fiscal dominance, where fiscal policy dictates all others: interest rates, exchange rates, trade policy, and even industrial strategy. Debt has grown so large that the Fed, ECB, and BOJ can no longer lead, but follow the bond market. Central banks now adjust to the needs of the Treasury, not the other way around. Monetary, trade, and industrial policies have become instruments of fiscal survival. Interest rates are no longer tools of macro management but reflections of fiscal constraints.

From there comes financial repression, the quiet confiscation of savings through inflation kept above yields. It is not policy failure but policy design. The purpose is simple: melt the debt in real terms. Yet as William White (ex Chief of the BIS) wrote in his 2023 essay The End of Certainty, financial repression is not neutral, it is a transfer of wealth from the bottom to the top. It rewards borrowers and asset owners, punishes savers and wage earners, and widens the social divide that monetary policy once pretended to soften. The same mechanism that stabilises sovereign balance sheets erodes the middle class. Repression preserves solvency at the expense of cohesion.

Once repression becomes structural, markets adapt. Investors stop fighting the system and begin profiting from it. That is the debasement trade: borrowing melting money to buy scarce assets. The numerator rises because the denominator dissolves. It explains why equities remain inflated despite stagnation, why property prices resist correction, and why gold surges even as real yields rise. Capital has learned that in the late-fiat era, the only hedge against policy is tangible value.

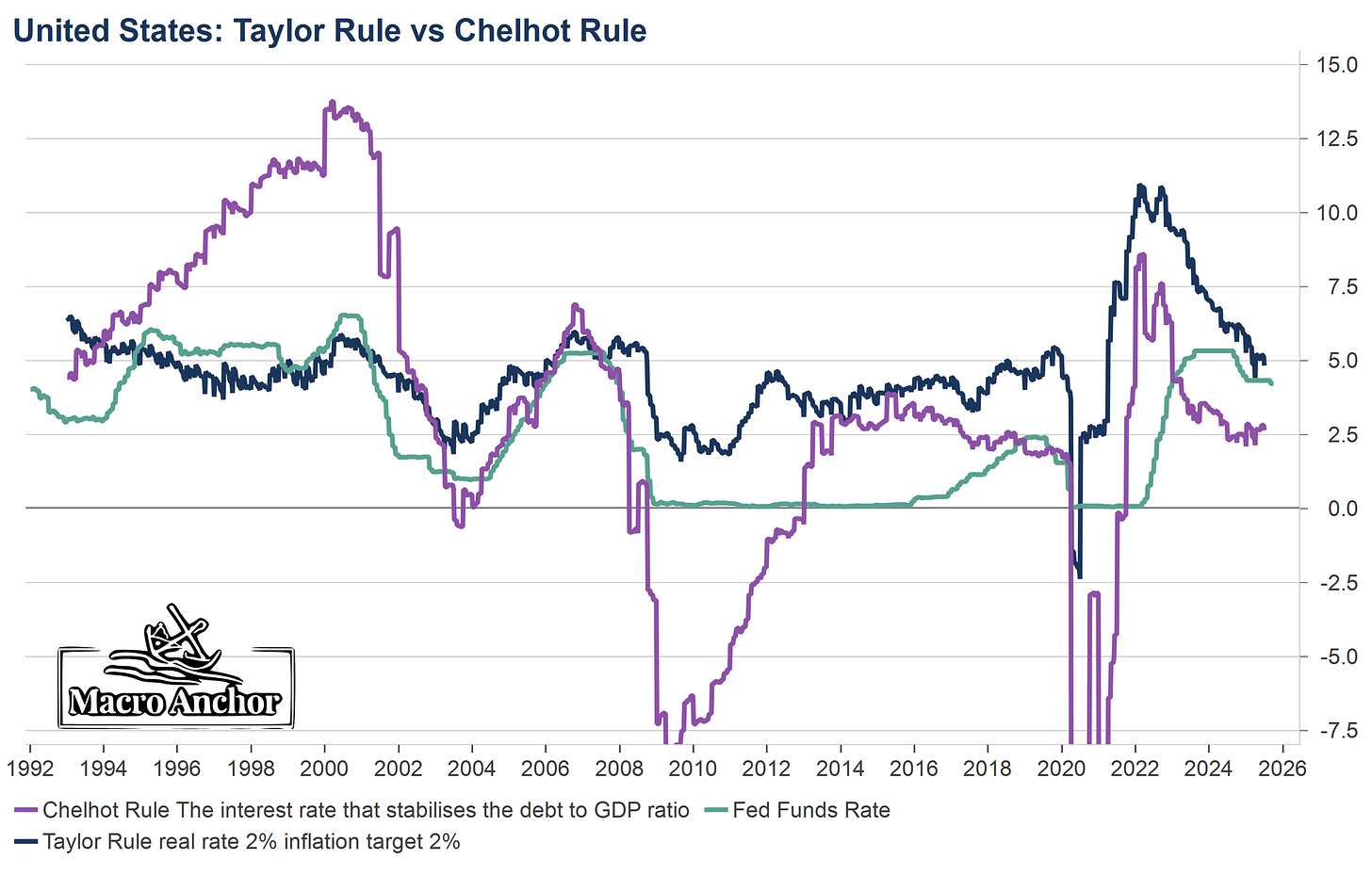

This new reality demanded a new rule. The Taylor Rule, the formula linking policy rates to inflation and output gaps, belonged to a world of independent central banks and price stability. That world no longer exists. What I proposed instead was the Chelhot Rule, the rule of fiscal reality. It measures the sustainability of the system, not the stability of prices. The Chelhot Rule defines the interest rate that stabilises public debt, given the economy’s nominal growth rate (g), its primary deficit (p), and its debt-to-GDP ratio (d). Formally,

r* = g - (p / d)

If the effective rate r rises above that equilibrium, debt becomes unsustainable; if it stays below, debt stabilises through growth and inflation. In this sense, the Chelhot Rule replaces the Taylor Rule as the true compass of modern policy. It explains why lower rates are no longer stimulative, they are fiscal containment, designed to prevent the interest bill from exploding. Monetary policy now serves solvency, not stability.

Tariffs belong to the same logic. They are not merely tools of trade policy; they are fiscal instruments. Tariffs are a tax, whether paid by domestic consumers or exporters. They raise prices, transfer income to the state, and finance deficits. Tariffs are inflationary in the short term and contractionary in real terms, a stealth form of taxation that turns trade policy into another pillar of financial repression.

Behind these mechanics lies the transformation of the post-1971 order. The petrodollar system once tied American paper to oil, giving the dollar global demand and the U.S. cheap funding. Every barrel priced in dollars was a claim on U.S. debt, every surplus recycled into Treasuries sustained the empire. But the structure that made the dollar king has evolved. The U.S. remains energy-independent, technologically dominant, and militarily unmatched, but the global system around it is fragmenting. China is the largest trading partner for most of the world, the Gulf’s surpluses now flow east, and a parallel architecture is taking shape.

That is how the idea of the Memodollar was born. The petrodollar linked money to barrels; the Memodollar links it to bytes and matter, to semiconductors, rare earths, and the strategic resources of the digital age. These are the inputs that define sovereignty today. Whoever controls them defines production, defence, and intelligence. In the twentieth century, power was measured in oil reserves; in the twenty-first, it is measured in chip capacity and mineral access. A currency backed by that strategic foundation carries credibility that paper alone cannot.

We are not heading toward the disappearance of the dollar but toward a bi-polar monetary order. One pole remains centred on the United States, a dollar system still backed by energy, military power, and high technology. The other is emerging across Asia, a bloc anchored by energy alliances, rare-earth dominance, and mass chip-making capacity. The first relies on confidence and security guarantees; the second on production and material collateral. Both will coexist, compete, and balance each other, defining the next monetary equilibrium.

Central banks are already adapting. The BIS writes about tokenised reserves and synthetic commodity money; the IMF calls it fragmentation and multipolarity. Gold has overtaken the euro in global reserves, a signal that the world is rebuilding trust in physical collateral before faith in fiat vanishes entirely. The next step is technological collateral: reserves implicitly backed by control of critical supply chains. Nations will no longer compete for yield but for access to energy, to data, to the raw materials of production.

Trade fragmentation is only the first stage. It will inevitably be followed by fragmentation of capital flows. If trade is settled in multiple currencies and collateralized by real assets, then savings, investment, and cross-border lending will regionalize as well. Capital will circulate within blocs defined by resource security and political alignment rather than by the illusion of a single global market. Net savers will live in a world of capital abundance, low funding costs, and deflationary forces; net investors and debtor nations will live in a world of capital scarcity, rising funding costs, and inflationary pressures. What began as a tariff war will end as a monetary partition, with cost of capital and price dynamics diverging sharply across blocs.

This transition is rarely acknowledged publicly because it is taboo in Western discourse. I saw that during my recent interview on Al Sharq News / Bloomberg Arabia. The anchor joked about Trump’s moods moving gold prices, and I turned the discussion to geopolitics and the future of the monetary order. The official summary that followed reduced the conversation to the “government shutdown and its effect on the U.S. economy.” The deeper point that gold rises because trust in paper is dying, never appeared. Western media can report symptoms such as yuan settlements or central-bank gold buying, but it cannot name the diagnosis: the slow erosion of the dollar-led world monetary order.

Inside institutions, however, the conversation is well under way. The IMF and BIS are already modelling a world of tokenised, collateral-backed currencies. They know that the post-1971 system replaced gold with trust, and the post-2020 system is replacing trust with collateral. This is not a market cycle; it is a monetary rewrite. Value is migrating back to things that exist: energy, minerals, and technology, and away from promises that can’t be kept.

When I wrote Trump’s Benjamin Strong Is Coming, I said the final bubble would not be financial but civilizational: the last act of monetary expansion before a redefinition of value itself. That moment has arrived. We are witnessing the birth of a new, bi-polar monetary order, one anchored in two systems of power, one based on energy and arms, the other on resources and manufacturing. Macro Anchor was created to chronicle, in real time, the end of the fiat illusion and the emergence of a world where money must once again be anchored to reality.

To all free readers: thank you for being part of this community. Macro Anchor remains fully independent: no sponsors, no institutions, only reader support. Starting at the end of October, full access to articles and analysis will be reserved for paid subscribers. If you’ve found value in this work, please consider upgrading your subscription today. It helps sustain the research, the data, and the time needed to stay ahead of the next turn in the global cycle.

Regards,

Andre Chelhot,

Editor

The Macro Anchor

Exceptionally well written, Andre! These two sentences distill the structural realignment of the global system as clearly as anything I’ve read lately.

"The U.S. remains energy-independent, technologically dominant, and militarily unmatched, but the global system around it is fragmenting. China is the largest trading partner for most of the world, the Gulf’s surpluses now flow east, and a parallel architecture is taking shape."